Background

As I mapped out my (Day – 5) route through Ladakh, I realized that Turtuk was a hidden gem, tucked away in a remote corner of the world. Turtuk is about 200 kms. from Leh, about 6 – 7 hr. drive. I was filled with excitement at the prospect of visiting Turtuk and Thang, the last villages on the Line of Control (LOC).

After soaking in the natural beauty of Tyakshi village, we set off to explore Turtuk. Nestled at an altitude of 9,250 ft., Turtuk is primarily inhabited by the Balti people, who have Tibetan roots. The village is divided into two sections – left and right, by a stream that eventually flows into the Shyok River.

As the stream rushes down the mountainside, the water flows powerfully over large boulders, creating grade three rapids that add to the village’s allure. This unique topography creates a stunning cascading waterfall just before the stream meets the river.

Strolling through the narrow lanes of left-bank Turtuk, I was struck by the old wooden frames adorning some of the houses. The small winding paths followed a perennial stream that gushed through the natural slopes, adding to the village’s picturesque setting. Here, I found a water-driven flour mill, a makeshift shed for goats, a local grocery shop, a village school, and all the essentials of village life.

Turtuk Heritage House & Museum

Walking through the village, we arrived at the Turtuk Heritage House & Museum, located on the first floor of a charming old weathered building.

This intimate one-room museum is a treasure trove, showcasing a fascinating collection of utensils, clothing, and artefacts that reflect the lives of local residents over the years.

Managed by Turtuk’s Women Welfare Society, the museum collects a modest entry fee, which goes directly to empowering village women to establish small businesses. Thanks to this initiative, many women from the village have opened cozy restaurants offering Balti cuisine, retailing beautiful woven sheep-wool shawls and garments, value-added products from local produce, particularly apricots, etc. I admired the warm shawls on display, but sadly, I had no more room in my luggage for souvenirs.

Yabgo Dynasty

Just a short walk away, we reached the Royal Palace of the Yabgo dynasty.

This two-storied palace, constructed entirely of wood in the 16th century, is beautifully adorned with vibrant paint and intricate carvings, speak of its regal heritage truly befitting a royal residence.

A majestic sculpted eagle guards the entrance, surveying visitors with an air of authority. Locally known as Yabgo Khar (the “Castle”), this historic site has weathered the tides of change, skillfully preserving its narrative through the transitions from monarchy to democracy.

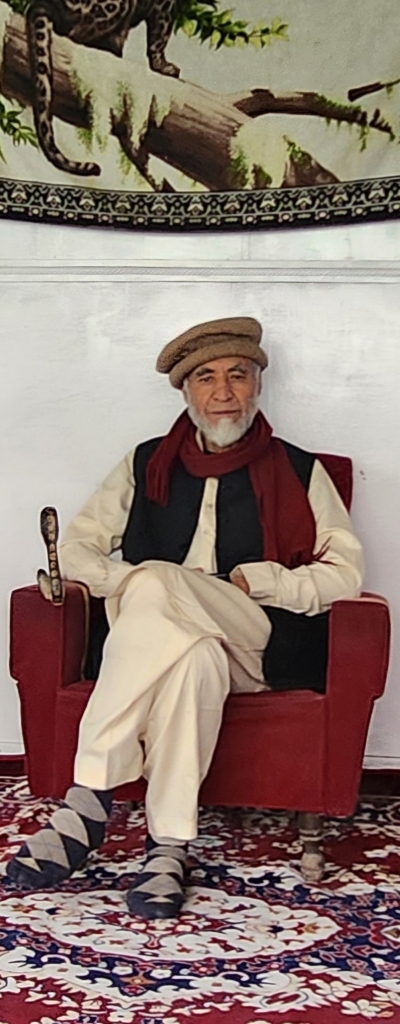

To our delight, we had the rare opportunity to meet His Royal Highness (HRH) Yagbo Mohammad Khan Kacho, the current King of Turtuk.

In an endearing display of humility, he referred to himself as “zamindar”, acknowledging that his lineage has faded and he has no kingdom to preside over nor subjects to govern.

His unofficial status of a king derives from the legacy of the Yabgo dynasty, a lineage beautifully illustrated on the wall in a display titled “The Pedigree of Rajas of Yabgo Dynasty Chhorbat Khapulu Baltistan”.

With a charming smile, he welcomed us warmly. He took his place on a makeshift throne, a sight that felt straight out of a storybook. As we sat on a couch opposite him, I felt honoured to engage in conversation with royalty.

In true regal fashion, he wielded a wooden sceptre adorned with a distinctive metal serpent head. The only other time I have brushed shoulders with nobility was when I shared high tea with the exiled princess of Afghanistan in my hometown of Kalimpong.

Here, surrounded by history and tradition, I felt the weight of the past intertwining with the present, creating a moment I would cherish forever.

A king sitting with me dressed as a common

Palace tucked in a corner amidst dingy village by-lanes

Rose and fountains once flourished

in backdrop of mighty mountains

Pointing to the intricate royal genealogical chart, the king shared, “Yabgo” is the surname of the first ruler of the Ghaz tribe. Prince Tung, the founder of the Yabgo dynasty, once commanded a vast territory that stretched from the borders of Afghanistan all the way to western Turkistan (a province in present-day Kazakhstan). He estimates that the Ghaz tribal rule began around 2,000 to 2,500 years ago.

In the 8th century, Beg Manthal, the tenth descendant of the Yabgo dynasty, journeyed from Yarkhand (in the Xinjiang region of China) and conquered Khapulu, which is now part of modern-day Gilgit-Baltistan. Over the centuries, the Yabgo seat of power gradually shifted from Central Asia to the rugged landscapes of Baltistan.

As the king proudly recounted the saga of his dynasty, he explained that according to ancient custom, the eldest son of the reigning king was to inherit the throne. However, during the era of Muqeem Khan, the 26th generation, this tradition was set aside to appease his powerful and beautiful second wife. In a bold move, the king divided his kingdom in two so that his younger son could also be crowned as a prince.

From that point onward, the dynasty experienced numerous subdivisions, gradually eroding its power and control over the region. Yabgo Rahim Khan emerged as the last ruler of the Turtuk-Chhorbat area. The dynasty’s final chapter closed with his death, marking the end of an era as the Dogra Empire seized control, ultimately forming the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

HRH Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho shared with us that the current palace in Turtuk once served as the summer capital of his empire. The main palace of the Yabgo dynasty still stands in Khapulu, a region that now lies beyond the LOC.

He reminisced about the Turtuk palace glory days, when it was surrounded by lush gardens adorned with fountains, beautiful orchards, and sprawling fields. From the palace balcony, one could gaze upon the Shyok River – a breathtaking view I could only imagine during its heyday. Now, however, the gardens and fields have been encroached upon by the villagers, and the once-proud palace struggles to maintain its dignity amid a sea of modest homes, clinging to its beauty and its place in the chronicle of history. The “Jarukh,” or the balcony, where the king once addressed his subjects, has now been repurposed as a lounge area.

Inside, the ground level features several distinct rooms: the Balti (men’s living room), Duk-nang (kitchen and storeroom), and Nhyal-sa (rooms for women, particularly pregnant women). This made me wonder if the Hindi word “Nanihal” shares any connection with “Nhyal-sa”. Each room was equipped with small windows and a rudimentary heating system.

Ascending from the courtyard, we entered the museum, which houses a fascinating collection of bows and arrows, maps, shields, lapis lazuli-encrusted swords, portraits, paintings, family record books, clothing, footwear, headgear, and even stuffed hunted animals. These dusty artefacts are the only remnants of Baltistan’s royal legacy. Much like the entrance gate, the museum features a large stuffed eagle, likely an emblem of the Yabgo dynasty.

As I explored the palace, the thick, cracked wooden beams and pillars, the delicate staircase and arches, the dusty window carvings, and the worn-out, bright carpets all whispered stories of a bygone era. The sinking couch, where the wooden frame was all too palpable, felt like a time capsule, inviting us to reflect on the rich history that once thrived within these walls. The small courtyard was vibrantly painted, adding a splash of colour to the historical structure.

HRH Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho expressed his deep concern that the younger generation shows little interest in upholding the legacy of the Yabgo dynasty. Instead of embodying a non-existent kingdom, they opt for the simplicity of common life, pursuing their own passions and choosing the vibrant allure of city living over the tranquil beauty of Turtuk. I found myself in agreement with his children’s choices, embracing the principle of living in the present rather than clinging to a faded notion of royalty. Moreover, the thrill of wandering the city streets incognito, like a common man cloaked in royalty, held a certain charm.

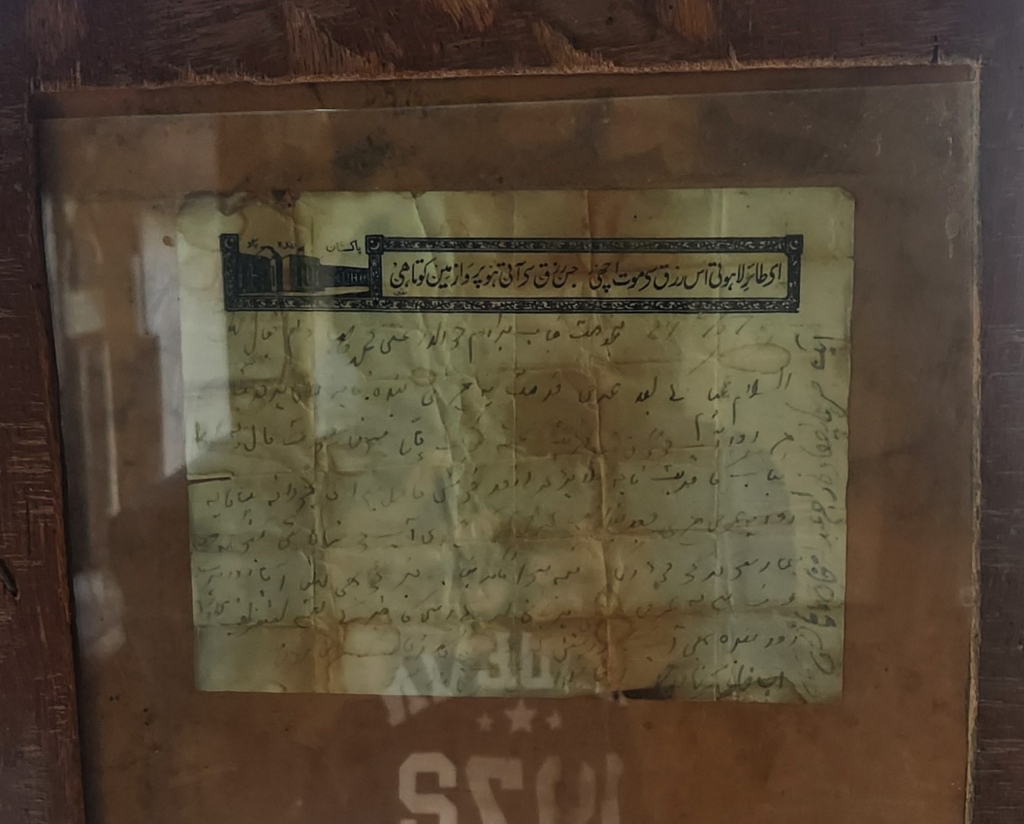

As the king regaled us with tales from a bygone era, I felt like a captivated history student, hanging on every word. He shared that after the partition, the Pakistani army occupied the palace, converting it into a military headquarters. His father bravely filed a lawsuit in the Lahore High Court, contesting the army’s illegal occupation. After a protracted legal battle, justice prevailed: the court ruled in his father’s favour, ordering the army to vacate the premises and directing the Pakistani government to pay Rs. 5 monthly for living expenses. This landmark Lahore High Court ruling is proudly framed and displayed as one of the museum’s artefacts.

However, the king’s voice grew somber as he lamented that before vacating, the Pakistani army had looted and ravaged the palace, leaving behind a shell of its former glory. The echoes of history resonate deeply within these walls, a bittersweet reminder of both loss and resilience.

As more guests began to arrive, the king graciously turned his attention to his other “subjects”. Among them were two tourists from the United States who, unfortunately, didn’t understand Hindi. Stepping into the role of translator, I happily took on the task of conveying the king’s captivating tales of his dynasty. We wished HRH Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho abundant health and prosperity, our words laced with respect for the history he represents.

In a gesture that caught me by surprise, the king presented me with his autograph, signing as the last known non-functional King of the Yabgo Dynasty – an echo of a realm that once was. It felt surreal to receive this token, a piece of history from a man who carries the weight of his ancestors, even without a kingdom to call his own.

If you’re planning a trip to Ladakh or the stunning Nubra Valley, don’t miss the opportunity to stop by Turtuk and meet HRH Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho – it’s an experience I highly recommend!

A stroll through the village of Turtuk offers a fascinating glimpse into traditional village life, rich with local customs, crafts, foods, and daily routines often overlooked in our modern world. It seemed that not many Indian tourists venture to this part of Turtuk village, making the experience all the more special. I suggest you dedicate 3 to 4 days in Nubra Valley to fully immerse yourself in its wonders. This way, you can explore Thang at the LOC, Diskit, Hunder, Panamic, and Siachen – an unforgettable journey that promises memories for a lifetime.

Feel free to write to me at connect@happyhorizon.in if you’d like to customize your Ladakh adventure.

August 2024

Gallery

Sukumar Jain, a Mumbai-based finance professional with global experience, is also a passionate traveler, wildlife enthusiast, and an aficionado of Indian culture. Alongside his career, which includes diverse roles in international banking and finance, he's working on a wildlife coffee table book and enjoys sculpture and pottery. His interests span reading non-fiction to engaging in social and global networking.

1 Comment

Anusha

Very beautifully written