Day 8 (Part 2): Rezang La – Read More

Day 8 (Part 3): Hanle

Rezang La – Tsaga La – Thangra – Loma – Hanle : 100 km. / 2.30 hr. / Altitude – 13,500 ft. (Hanle)

Rechin La

As we departed from Rezang La, our hearts were heavy, having paid our respects to the fallen soldiers, the heroes who once guarded these lands with their lives. The journey ahead began with the weight of those memories, yet the stark beauty of Ladakh began to take hold of us.

We drove through a barren yet mesmerizing landscape, where the terrain alternated between dry, rugged expanses and unexpected patches of green. The mountains stood tall, stripped of vegetation, save for the occasional crown of snow clinging to their peaks. There was no sign of life for miles, and the silence of the land felt like a canvas of nature’s most primal colours – earthy browns, deep greens of scant foliage, and the soft blue of a cloud-dappled sky. The emptiness seemed to question the logic of war and death in such desolate beauty. It was just us and the wild elements.

Crossing into the conflict-laden region of Rechin La, we drove through shallow streams that snaked across our dirt track. A couple of motorbikes were parked on the other side, their riders waiting patiently for the engines to dry after the water had seeped in. We pulled over to offer help, but they assured us the bikes would be fine in time. Instead, they had chosen to sit back, snack in hand, and savor the scenery. They knew something about life that many miss – it’s the small moments that matter. For all the allure of motorbiking, I knew my heart belonged to four wheels and the dream of longer, rustic journeys ahead, perhaps across the deserts of Rajasthan.

Golden Duck Lake

A short drive later, we stumbled upon Golden Duck Lake. Its name was inspired by the migratory Ruddy Shelducks – those Brahminy ducks (Indian name) that grace its waters in winter. This shallow snowmelt lake, lay in peaceful solitude, as though waiting for its feathered guests to give it purpose once more.

Further down the road, we came across a large, serene grassland where flocks of sheep grazed. The scene felt otherworldly, a surreal oasis in this otherwise harsh and unforgiving landscape. Nearby, a handful of local labourers worked diligently, reinforcing a small bridge over a babbling rivulet. It was a rare relief to see people after miles of solitude. We stopped briefly, exchanging smiles and chocolates with the children.

Tsaga La

Next, Tsaga La loomed into view, towering at 15,620 feet, imposing its presence on the LAC. The tension in the air was almost tangible – a stillness that was hard to shake. The rugged beauty felt tinged with the tension of a borderland, a place where survival is a daily endeavor, whether for humans or the wild creatures that roam here. A small gompa stood at the pass, but not a soul could be seen.

As we descended from Tsaga La, the vast Thangra Valley unfolded before us like a scene from another world. The valley stretched on and on, bound by distant peaks that appeared as if they had been flattened by the sheer distance between us. There was no horizon here, just an endless expanse of land, blending trans-Himalayan golden desert and aristocratic pastures, merging into the mountains. It felt like the very edge of the world, and for a moment, it was as if time itself had come to a standstill, allowing us to bask in the sheer enormity and quiet grandeur of the landscape.

As we descended from the rugged heights to the vast plains, the dirt track vanished as if swallowed by the earth itself. In that moment, it felt as though we had strayed beyond the reach of any discernible path. To our left loomed the LAC, a boundary imbued with silent tension, so we instinctively turned right, directionally seeking a way forward. Those next ten minutes were the most eerie of our entire journey – an unsettling stretch where the absence of a road stirred an inexplicable unease. Why had the track disappeared so abruptly? I could only wonder.

Fortunately, after a slow, careful crawl across the barren land, we spotted a vehicle far in the distance. The land stretched out flat and wide, free of obstacles, so we made a beeline towards the lone truck. It turned out to be a tar-laden truck, part of an ongoing roadwork project. As we approached, the road reappeared like a forgotten friend, guiding us onward. Soon enough, we found ourselves entering the village of Thangra, the landscape softening, offering promise and reprieve.

Thangra & Indus River

Here, the mighty Indus River joined our journey, flowing alongside us with a serene, almost careless grace. The land, so flat and expansive, allowed the river to spread wide, its broad banks fringed with lush green pastures. We began to see animals grazing lazily in the fields – cattle, horses, and the occasional Kyang, that enigmatic wild ass of the trans-Himalayas.

The sight of a Kyang racing alongside our vehicle was something surreal, though it seemed more out of startled fear than playful competition. In a gesture of respect for its wild, untamed spirit, we let it claim victory in our unspoken race.

There was something haunting about the Kyang grazing alone in this vast solitude, no companion in sight for miles. It reminded me of Aristotle’s words:

“Whosoever is delighted in solitude is either a wild beast or a god”

In that moment, I felt a kinship with the solitary Kyang. Since I am certainly no god, it was easy to imagine both of us as wild creatures, unshackled by society, untamable by any force. For some, this blissful solitude, if embraced over time, can lead to enlightenment, much like Buddha.

The Kyang remains a creature of wild independence. A species of wild ass, it lives without human interference, finding its own food and water, thriving in the harsh trans-Himalayan cold deserts, often near marshes or wetlands. There is no history of humans taming the Kyang – it is a beast that has forever eluded domestication, as free as the wind.

Located near the Tibetan border, Thangra has long enjoyed a rich history of trade with its neighbour. Yet with the introduction of the LAC, the village’s traditional way of life has been disrupted. Many of the villagers have begun shifting towards a more commercial existence in Leh, their fates altered by the invisible lines that now define borders and destinies.

As we pressed on, we encountered a small crossroad, an unexpected fork in the dirt track. A milestone and a signboard stood side by side, pointing towards destinations neither of us had ever heard of. Was this the turn towards Umling La via Koyul? The road ahead looked uncertain, uninviting, and there wasn’t a soul around to ask. The risk of unknown around LAC heightened our caution, so we decided not to risk a wrong turn.

As I lingered by the milestone, I couldn’t help but think of Heena, my school friend. I snapped a picture of it to send her – small tokens like this bridge our journeys with those we cherish.

Loma

We paused briefly behind a lumbering truck at Loma, its heavy cargo of rations destined for Hanle, our own endpoint. Loma stands as a quiet but crucial junction, where one road veers right toward Nyoma, and another leads deeper into the remote heartlands, toward Hanle. As we considered our route, I couldn’t help but think of the adventure we might have missed if we had taken the Nyoma path from Merak – we would’ve bypassed the wild, rugged beauty of the plains around Thangra, a landscape that had filled us with adrenaline and awe.

At Loma, we asked about a possible detour to Umling La via Koyul. A bystander, rugged and seasoned by the harsh terrain, offered to guide us since he was heading toward Koyul himself. His warning, however, that the road was rough and unforgiving. Danish preferred the comfort of the well-tarred road, and after a moment’s hesitation, we decided to play it safe, steering towards Hanle directly.

As we took the turn, the terrain shifted beneath us, the dirt track giving way to smooth blacktop. The road carried us past the serene village of Loma, where bright green fields stood out against the barren landscape, and the Hanle River meandered lazily, separating us from the village.

Amidst this quiet, two villagers suddenly appeared, sprinting across a bridge, waving frantically in our direction. Perplexed, we pulled over to wait. The leaner of the two outpaced the other, the gap between them widening with every step. When they finally reached us, panting and out of breath, they asked if we could give them a lift to Hanle – they had missed the last state bus. We welcomed them aboard, happy for new company. Every hitchhiker we had met so far, starting with Gopal @ Kargil, had brought their own brand of entertainment, a welcome distraction from the repetitive soundtrack of our road trip.

Hanle

The road ahead unfurled, freshly laid with a smooth layer of black tar, winding its way into pristine hills untouched by permanent human habitation.

Occasionally, we’d spot herdsmen tending to their flocks of Changthangi (Pashmina) goats, a gentle reminder that this land, though desolate, was not completely deserted. As we ascended higher, the vastness of the landscape became almost overwhelming – a horizon that seemed to stretch endlessly. We were still about 50 km. away from Hanle, a leisurely hour and a half drive, giving us plenty of time to chat.

Our two new companions, both locals from Loma who worked at the Indian Observatory Centre in Hanle, filled the time with stories of their lives between these two remote outposts. They were a godsend, offering not only insight into the Observatory but also guiding us on how to visit it before heading to our homestay. They mentioned how Hanle had been declared a Dark Sky Preserve, a sanctuary for stargazers and astronomers alike. Since this designation, tourism had surged, bringing more attention to this otherwise secluded region.

Eventually, we stopped at a small cafeteria operated by the Indian Army, a simple but welcome sight in the middle of this desolate expanse. Our fellow travelers graciously agreed to a tea break. I, as usual, opted for coffee – an easy choice when the risk of messing up milk-to-coffee ratios is low. Tea, on the other hand, can be an unpredictable affair. As I scroll through the photographs from our journey, I can’t help but chuckle at the sight of two dragons decorating the café. They’re certainly not part of Ladakhi tradition, but I can’t shake the humorous thought that perhaps it’s the Indian Army’s symbolic way of “petting the dragon” at the Line of Actual Control.

The army personnel manning the cafeteria was apologetic; many items on the menu were out of stock, as the chef had rushed back to his village for an emergency. In his absence, two hastily trained cooks had been left to handle tea, coffee, and Maggi – bare essentials for hungry wanderers like us, but enough to keep the journey going. As we sipped our drinks, the Hanle Monastery came into view, perched serenely on a distant hillock, watching over the valley.

The main draw of the cafeteria, however, wasn’t the tea or snacks, but the free Wi-Fi – courtesy of the army’s own spectrum. In this remote wilderness, far from mobile networks, it felt like a true lifeline, a service to all passing travelers. Just like at Rezang La, the café here featured a few props for a makeshift photo booth. We snapped some pictures, capturing the moment before resuming our trek towards Hanle. I made a lighthearted promise to the jawan at the counter – whether for food or just free Wi-Fi, we’d be back at the café every day.

The Indian Astronomical Observatory

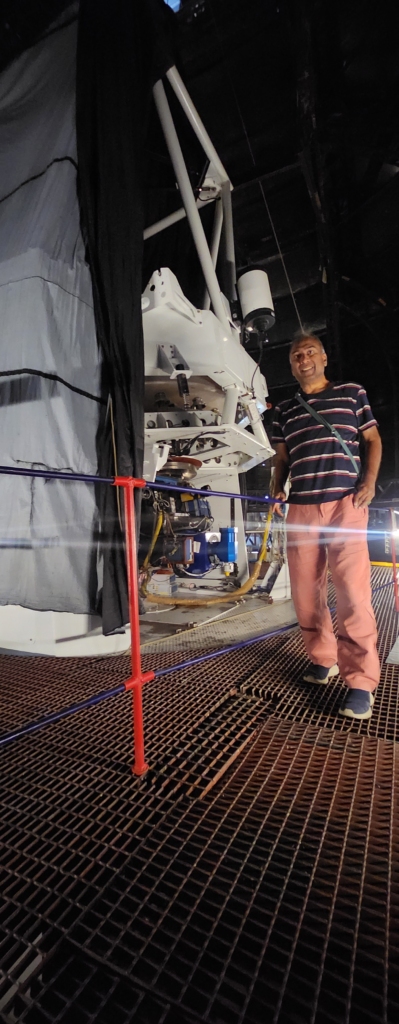

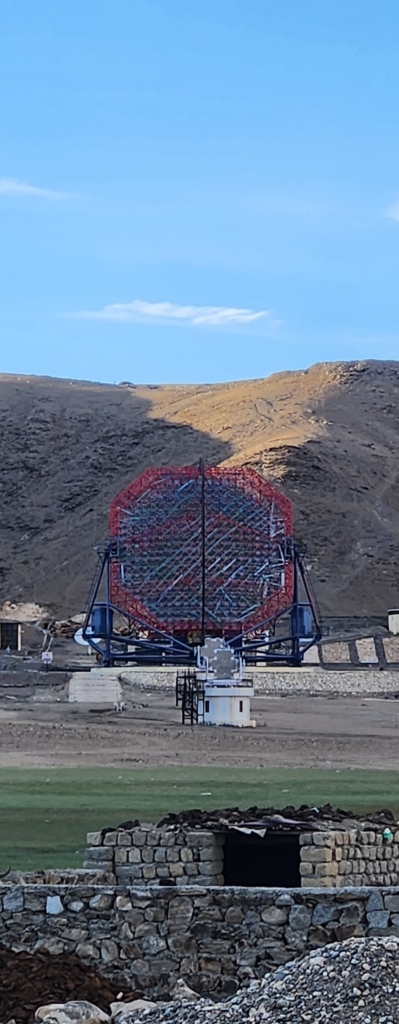

Our two local companions had some errands to run, so after dropping them off, we headed straight for Mt. Saraswati in Hanle, home to the renowned 2-meter optical telescope. This marvel of science, remotely operated by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics in Bengaluru, connects to the universe via a dedicated satellite link. As I admired the telescope, I couldn’t help but reflect on its significance – it’s one of the highest astronomical observation points on the planet, designed to study the mysteries of the universe.

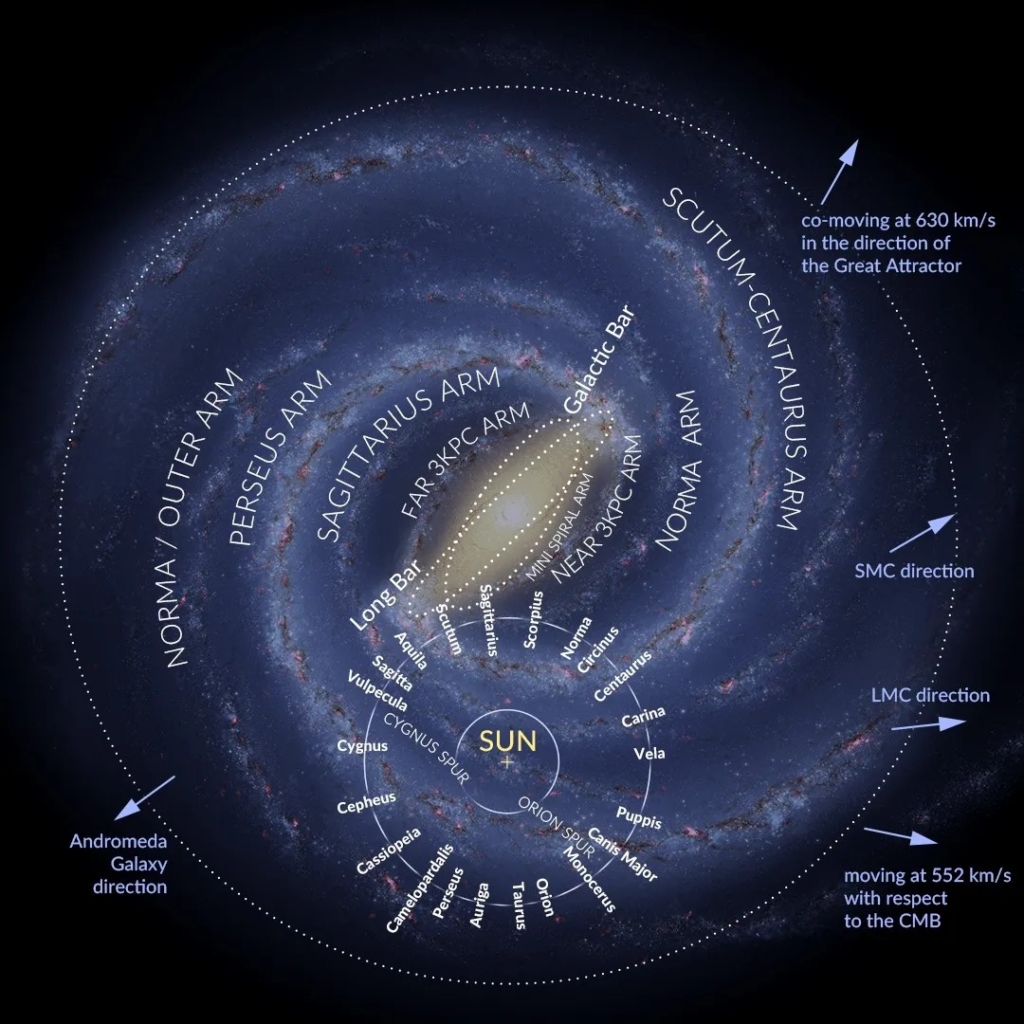

This optical telescope, gathering light from the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum, allows scientists to capture images of celestial objects, much like photography in space. Scattered around the area are other telescopes as well, ones that capture infrared and gamma rays, revealing the universe’s secrets in different wavelengths. As we explored the second floor of the complex, I found myself mesmerized by the sheer size and complexity of the instruments – an overwhelming sight for a non-scientific mind like mine. Yet, a question bubbled up from my basic understanding of astronomy. How, I asked the scientist stationed there, was it possible to take photographs of the Milky Way galaxy while we were inside it?

He laughed, amused by the simplicity yet importance of the question, and praised the curiosity behind it. As he explained, I felt a sense of pride rather than embarrassment. He described the Milky Way as a spiral galaxy, with several arms spiraling out from its core. Our solar system resides within the Orion Arm, a minor branch. The photographs we often see are not of the entire galaxy, but of its core – the Galactic Core and Long Bar, the bright hearts of our cosmic home. With this newfound knowledge, I was eager to see the night fall in all its glory. A clear view of the Milky Way was one of the main reasons we had ventured all the way to Hanle. Now, all we needed was for the sky to cooperate.

Homestay @ Hanle

Our homestay was perfectly nestled at the base of Mt. Saraswati, and our host, Kaisang, was as warm and welcoming as we could have hoped. He quickly settled us into a cozy room. As we discussed other attractions around Hanle, to my delight, he offered to take me on an early morning trek to try and spot the elusive Pallas cat – provided I could be up and ready by 5 a.m.

The skies remained cloudy, dashing our hopes for stargazing that night, but we kept our fingers crossed for clearer skies the following evening. In the meantime, the promise of tracking the Pallas cat had me excited for the next day’s adventure. That night, after an early dinner, we slipped into bed, tired but content.

August 2024

If you’re planning a trip to Hanle (via Thangra) or explore Ladakh, we at HappyHorizon would be thrilled to curate your holiday plans to enhance your travel experiences. Feel free to reach out to us: connect@happyhorizon.in

Day 9: Umling La – Read More

Gallery

Sukumar Jain, a Mumbai-based finance professional with global experience, is also a passionate traveler, wildlife enthusiast, and an aficionado of Indian culture. Alongside his career, which includes diverse roles in international banking and finance, he's working on a wildlife coffee table book and enjoys sculpture and pottery. His interests span reading non-fiction to engaging in social and global networking.