Day 7 – Day 8 (Part 1): Merak (Pangong Tso) – Read More

Day 8 (Part 2): Rezang La – Hanle

Merak – Chushul – Rezang La War Memorial: 40 km. / 1 hr. / Altitude – 16,400 ft. (Rezang La War Memorial)

Chushul

Our journey to Hanle, still a four-hour drive away, had taken us alongside the lake for several km. As we drove along the vibrant, mesmerizing stretch of Pangong Tso, its shimmering waters played with the sunlight in a way that felt almost otherworldly. But soon, the landscape shifted. The lake curved eastward, its deep blue fading into the distance towards Aksai Chin, and we bid farewell to the enigmatic beauty of Pangong Tso.

The smooth tar road gradually gave way to a bumpy dirt track, an unmistakable sign that we were entering more remote terrain. Before long, we found ourselves on the outskirts of Chushul, a tiny village seemingly frozen in time. The sun was high, and the road ahead presented a fork that demanded a decision. With no mobile signal and an offline map that I had forgotten to download, the choice was left to instinct. The streets were empty – no locals to ask, no other travellers in sight. We opted for the safer route, heading deeper into the village, only to be greeted by a dead-end.

Chushul, a sleepy settlement in the middle of nowhere, was a far cry from the modern conveniences we city dwellers often take for granted. Tar roads, streetlights, and infrastructure were absent, though solar panels dotted the occasional rooftop. It struck me that solar energy could be a lifeline for such isolated communities. The government, I thought, should consider sponsoring these remote villages, developing sustainable infrastructure that could serve as a model for others. Perhaps an initiative to bring city bureaucrats here could awaken a consciousness of the disparities between urban and rural lives—though it may seem like wishful thinking in a developing nation with endless priorities.

After retracing our steps, we took the alternate dirt track, praying it was the right one to Hanle. The barren landscape stretched out endlessly, hemmed in by mountain ranges on either side. The road – a faint, dusty car track – was our only guide through this desolation. Half an hour later, a rare vehicle appeared, confirming we were, indeed, on the right path. Our trip had mostly been on well-paved roads, even deep into Ladakh’s hinterlands, so I had assumed this path would be no different. But here we were, on a spooky, deserted stretch with nothing but tire tracks and towering mountains for company. The reason for choosing this route was my curiosity to explore a potential detour to Umling La without passing through Hanle, hoping to uncover the uncharted region of Koyul. For the faint-hearted there is an alternative tarred route to reach Hanle via Chumathang – Nyoma.

Rezang La War Memorial

And then, out of nowhere, we saw it: Rezang La War Memorial. It was an unexpected find – a surprise that broke the monotony of the eerie wilderness. We debated whether to stop. The vast emptiness around us didn’t exactly encourage unscheduled breaks. This wilderness felt like no man’s land. But perhaps this was an opportunity to confirm we were still on the right track to Hanle. In the end, curiosity won. We pulled over and approached the memorial. It felt deserted, its remote location attracting only the most adventurous of souls willing to stray from the beaten path.

By the entrance, a photo booth offered visitors the chance to don military outfits for pictures—a brilliant idea that should be replicated at every war memorial, I thought. I hadn’t known much about Rezang La or its significance; it wasn’t even on our itinerary. But as we stood before the memorial, in the heart of this isolated and forgotten landscape, I sensed that I was about to learn something profound.

We parked ourselves in a quiet canteen, waiting for a few more travellers to join us for the guided tour of the Rezang La War Memorial. Before long, a small group of tourists arrived, and after a quick registration, an army guide – stoic and brimming with pride – began leading us on a journey through history.

Our first stop was a modest tombstone, marking the memory of 114 brave soldiers who laid down their lives defending the Rezang La post when China attacked India in November 1962. I had studied the 1962 war in school, but hearing about the Chinese aggression at the very site where it happened was something else entirely – it brought the pages of history to life.

Charlie Company to “Rezang La Company”

The military guide explained that once the threat to Chushul was realized, the 13th Kumaon Battalion was rushed in from Baramulla. Rezang La, a strategic pass lies close to the India-China border, making it a highly sensitive area. Chushul at a distance about 12 km. had an airstrip, a crucial link toward Leh, and so the singular mission for the battalion’s Charlie Company was clear – protect the airfield at all costs.

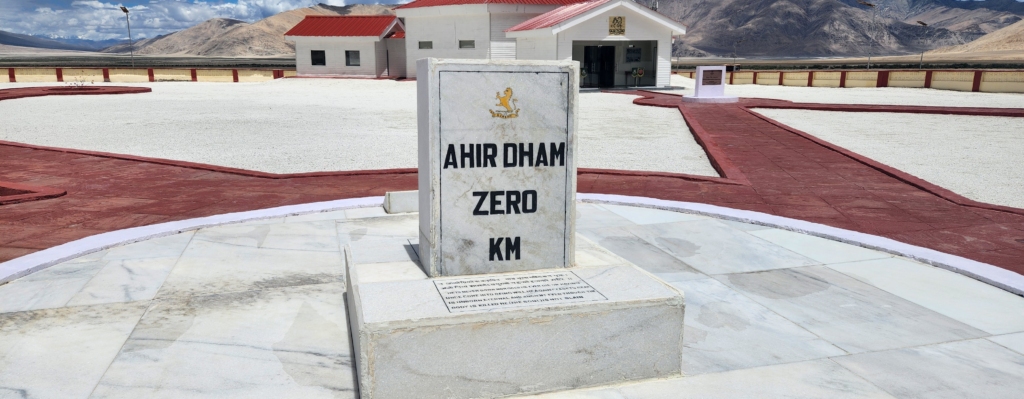

The C (Charlie) Company, led by Major Shaitan Singh Bhati, comprised 124 soldiers, majorly from the Ahir community, which hailed from the plains of Ahirwal region of Haryana. The military command’s message was simple but a daunting task: hold the Chinese forces at Rezang La. The Chinese launched their assault on November 18, 1962, but despite overwhelming odds, the soldiers of C Company fought valiantly until nearly every last one of them fell. Of the 124 men, only six survived, and those who did were taken as prisoners of war. The battle was so fierce, so heroic, that the Rezang La Memorial is also known as Ahir Dham in honour of these brave soldiers, and Charlie Company was later renamed as “Rezang La Company”.

The Supreme Sacrifice

Our guide continued with reverence, sharing that this was one of the first major battles fought at such a staggering altitude – 17,000 ft. The Chinese, long trained in the freezing Tibetan plateaus and armed with modern semi-automatic rifles, had a distinct advantage. By contrast, the Ahirs from the plains of Haryana had only outdated rifles from the World War II era, and most of them were seeing snow for the very first time. They did not have any time to acclimatize. Yet, it was their indomitable spirit that made the Chinese witness grit and courage like never before. The memorial stands at the very place where the 114 fallen soldiers were cremated.

The guide recounted the heart-wrenching stories of the battle, as told by the six prisoners of war who miraculously survived. When Rezang La was revisited after the battle, the bodies of every single Indian soldier were found in their trenches, weapons still clenched in their hands, having fought to the very end.

There were tales of extraordinary bravery. A medical orderly was shot while tending to the wounded, and when his body was found, he still clutched a morphia syringe and bandage in his hands. One soldier, killed in a crouching position, had been rushing between sections when a bullet struck him down. Another, a mortar man, was found dead with a bomb still in his grasp – of the thousand mortar bombs fired during the battle, only seven were left unused. Naik Ram Singh, a wrestler from the battalion, took down several Chinese soldiers with his bare hands before he, too, was shot in the head.

But it was Major Shaitan Singh Bhati who stood as a towering figure in this saga of valor. Posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India’s highest military honor, his courage was nothing short of legendary. He moved from platoon to platoon under heavy fire, rallying his men and personally engaging the enemy. Completely ignoring his own safety, he fought like a man possessed, determined to hold the line at Rezang La.

As the guide narrated these stories of courage, a chill ran down my spine. I could feel the weight of their sacrifice pressing down on me, each tale more profound than the last. It was overwhelming, almost incomprehensible, that such men had walked this earth – here, in this desolate yet sacred land, they fought with a strength of spirit that seemed beyond human capacity.

Captain Prem Singh, who witnessed the battle from Tsaka La, once described the scene: “I saw missiles with flaming red tails falling on Rezang La. The entire Rezang La feature was on fire”.

Standing there, beneath the vast, quiet sky, surrounded by the barren mountains of Ladakh, the weight of history settled in. The battle of Rezang La wasn’t just a story of loss, but a tale of unspeakable bravery, where men stood firm against the odds for their country, for their comrades, and for their honour. And here, at this humble war memorial, their legacy endures.

The tombstone at Ahir Dham had this verse from the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 2, Verse 20.

na jāyate mriyate vā kadāchin

nāyaṁ bhūtvā bhavitā vā na bhūyaḥ

ajo nityaḥ śhāśhvato ’yaṁ purāṇo

na hanyate hanyamāne śharīre

Here, Lord Krishna explains the nature of the soul (Atman) to Arjuna. The verse translates as:

He (Soul) is never born nor Does He Ever Die, Or Having Once Come Into Being Will He Again Cease To Be He

Is Born Eternal And Ancient Even Though, The Body Is Killed He Is Not Slain

The verse emphasizes the immortality of the soul, highlighting that death only affects the body, not the soul. The soul is beyond birth, death, and time, and remains unchanged despite the destruction of the physical body. Lord Krishna reassures Arjuna that his duty in battle will not destroy the soul, which is indestructible and eternal.

The War Memorial – Ahir Dham stands as a fitting and solemn tribute to the ultimate sacrifice made by the brave soldiers of Rezang La. As we walked through the memorial, guided by an army officer, the tale of November 18, 1962, began to unfold – a day etched in history and shadowed by immense valour.

The Chinese Misadventure – November 1962

The Chinese troops had quietly amassed in forward positions under the cover of darkness, intending to launch a surprise assault at dawn. As the first wave of attackers advanced into range, the soldiers of Charlie Company opened fire, fiercely resisting the initial onslaught. When couple of frontal attacks faltered, the Chinese began shelling Rezang La, mercilessly bombarding the Indian position. The fire was relentless; no trenches withstood the brutal barrage.

The battlefield topography denied them any meaningful cover or support. Charlie Company was isolated, exposed to the elements, and left to fend for themselves – without backup, without escape, and without hope of reinforcement. Listening to the guide and absorbing the terrain around us, it became painfully evident: the soldiers who fought that day knew they were up against impossible odds.

Yet they fought on.

Deeper into the memorial complex stands the Remembrance Wall, engraved with the names of the 114 heroes who gave their lives in that desperate battle. It is a powerful reminder that nations are not merely built on policies or borders, but on the blood, grit, and sacrifices of those who defend them. The men at Rezang La were woefully underprepared for the brutal conditions they faced – clad only in thin sweaters, with wet shoes in the bone-chilling cold of -30°C at an altitude of 17,000 ft. The sheer endurance required to even exist in such harsh conditions is unimaginable – let alone to fight with such unwavering determination.

In front of the Remembrance Wall, a tombstone erected by the 13th Battalion of the Kumaon Regiment solemnly reads: To the sacred memory of the heroes of Rezang La 114 martyrs of 13 Kumaon who fought to the last man last round against hordes of Chinese on 18 November 1962 –

How can a man die better,

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods.

This verse is from Thomas Macaulay’s poem “Horatius”, part of his work Lays of Ancient Rome (1842). The lines are often quoted to emphasize the honour and heroism in dying for noble causes, such as the defence of one’s heritage and sacred beliefs.

The verse suggests that the noblest way for a man to face death is in the defence of things that matter most – his heritage and his faith. It glorifies the sacrifice made for preserving the values, traditions, and beliefs that define a person’s community and identity. Dying for such causes is seen as the highest form of honour, even when the odds are against survival.

As I stood before the tombstone, reflecting on the soldiers who once stood here, I was struck by the weight of their courage. This war memorial is not just a reminder of what was lost, but a celebration of what was held: honour, duty, and the indomitable spirit of those who refused to give in, even when the battle seemed already lost.

Further every battalion carries with it a unique identity – a highest honour, a battle cry that echoes through time, and a motto that drives each soldier forward. Yet, at the heart of every Indian soldier is an unwavering dedication to protect the sovereignty of the nation. Their ethos, encapsulated in the words “Naam, Namak, Nishan” – name, loyalty, and flag – guides their every action, even in the face of death.

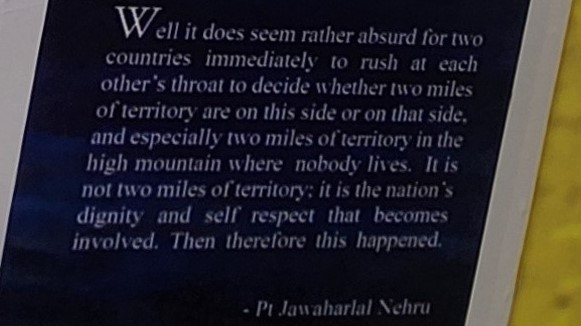

In the Visitors Gallery, as you stand above a scaled model providing a panoramic view of the war zone, you can almost feel the weight of history pressing down. The desolation of the terrain, the isolation of the battleground – it all comes into focus. As I reflect on the events of that fateful day, I find myself questioning the purpose of it all. What, truly, did the Chinese Army accomplish here? Beyond capturing a few barren, tactical positions in an inhospitable land, what was gained? Was it worth the devastating loss of life, both Indian and Chinese? Just three days after the bloody conflict at Rezang La, on November 21, 1962, the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire. The reasons for the ceasefire seem irrelevant now, but the lingering question remains: how cheap has human life become?

The landscape around the memorial is silent now, but it wasn’t always so. On that morning in 1962, the air would have been filled with the thunder of artillery fire, the cries of soldiers, and the relentless determination of men who knew their cause was just. Their sacrifice was monumental – each life given not in vain, but in defence of something far greater than themselves. At the very least, the Chinese will now think twice before attempting any further misadventure.

This story is not one of conquest or glory. It is a tale of unimaginable sacrifice – of men who faced impossible odds and knew, almost from the start, that they were fighting a battle they could not win. Yet they stood their ground, willing to lay down their lives without hesitation. These were Indian soldiers who stared death in the eye and did not flinch. They held the line at Rezang La, not for personal gain, not for victory, but for honour, duty, and the sovereignty of their homeland.

This is the story and history of Rezang La.

August 20224

If you’re planning a trip to Rezang La War Memorial or explore Ladakh, we at HappyHorizon would be thrilled to curate your holiday plans to enhance your travel experiences. Feel free to reach out to us: connect@happyhorizon.in

Day 8 (Part 3): Hanle – Read More

Gallery

Sukumar Jain, a Mumbai-based finance professional with global experience, is also a passionate traveler, wildlife enthusiast, and an aficionado of Indian culture. Alongside his career, which includes diverse roles in international banking and finance, he's working on a wildlife coffee table book and enjoys sculpture and pottery. His interests span reading non-fiction to engaging in social and global networking.